Trades and Konas (originally posted to the Road Runner website, 12/04)

By Neal Miyake When I was young, I never appreciated how much the wind affected surf conditions. I just went to the same surf spot without considering wind direction and strength. However, now that I'm older and (sukoshi) wiser, I know a little better. By learning some basic meteorology and using a few resources, anyone can maximize surf quality by understanding the wind. Straight off, I would like to acknowledge several meteorologists for their generous help and support, including: Pat Caldwell of NOAA/NCDDC, Hans Rosendal (formerly of the NWS) , and Dennis Nullet of KCC. This rather lengthy article will describe global weather systems, coastal ramifications, daily wind changes, and how they apply to surf conditions in Hawaii. For basics on how winds create swells, see "Wassup Wit Da Buoys" (currently unavailable) .

Here's a little bit of Meteorology 101 to put things in context. Take special note of the terms so the next time you hear Shari, Guy, Kathy, or Trini talk weather on the local TV news, they hopefully will make more sense. The uneven heating of the Earth's surface by the sun creates air pressure differences that inevitably form winds. Globally, air gets cycled in the atmosphere in fairly permanent "cells." Air is heated up more around the equator causing it to rise (convection), leaving an area of relatively low pressure. As it rises, it cools and moves outward to the poles in the upper atmosphere. Eventually the air sinks back down to the surface where a high pressure ridge (the center of a high pressure system) is formed. Since air moves from areas of high pressure to low, it then heads back towards the equator, completing the cycle. Various complexities contribute to worldwide wind patterns, including the Earth's rotation (the Coriolis effect), inclination (which inevitably produces the annual seasons), and land masses (disturbing airflow and creating large-scale convection).

For Hawaii, the cell that affects us the most is the north tropical cell, which cycles from the equator to around 20 to 40 degrees north latitude (usually north of Hawaii). The associated quasi-permanent high pressure ridge that sits north of the islands is called the East Pacific Ocean Subtropical High pressure center (or Hawaiian High). The surface winds flow from north to south and deflected (via the Coriolis effect) from east to west, becoming our ubiquitous northeasterly trade winds (wind direction is described by where it is coming from). In the northern hemisphere, the winds around a high pressure system revolve in a clockwise direction.

Btw, contrary to popular belief, trade winds were *not* so named because sailing traders used these winds. Actually, the word "trade" was once an adverb meaning "regularly and steadily in the same direction." Interesting factoid. The Hawaiian High is usually better established and at higher latitudes during the summer, so the trades are more stable (occurring nearly 90% of the time, vice around 50% during the winter). They usually blow out of the NNE to east at around 10-20 knots. However, if the high pressure system dips down right over the islands or if a migratory high (a more transitory system) passes nearby, the pressure gradient can go flat and the winds may turn variable (vary in direction or even be calm) or southerly. This is one manifestation of our infamous, humid Kona weather. See Dennis Nullet's high pressure page for a more comprehensive explanation. Low pressure systems also affect winds on a large scale. There are two kinds of lows: ones with fronts (boundaries between air masses of differing temperature) and ones without. In the northern hemisphere, low pressure systems have winds that flow in a counterclockwise direction around the low pressure trough (the center of the low pressure system). The migratory mid-latitude low pressure systems (with fronts) travel from west to east usually during the winter months. They bring air masses into contact and their boundary is called a front, typically with a warm front (with warm air behind it) followed by a cold front (with cold air behind it). The low pressure trough passes to the north with the fronts sweeping over the islands. During that time, the islands may see the winds rotate "around the compass," shifting from trades to southerlies to northerlies, then back to trades. (Interestingly, north winds are typically cold winds because they come from higher latitudes and higher altitudes.)

The other type of low is a low pressure system without fronts, which includes tropical depressions, tropical storms and hurricanes. They are not a product of warm and cold air meeting, but are formed over warm water, which causes air to rise creating the low. This type of system can produce very powerful winds, and usually have erratic paths that are difficult to predict. Fortunately, they are fairly uncommon in our part of the Pacific. What does all this gobbledygook mean to the average surfer? Well, by knowing the current and near-term weather conditions, you can actually forecast the winds on the coast to help you find optimum surf. You can also avoid potentially dangerous surf, especially from rapidly changing weather conditions. Land topography can change wind directions locally. The mountains and valleys on the islands redirect and funnel winds (increasing wind velocity). Also, because of sheltering, winds may vary significantly from one place to the next. As a surfer you need to be aware of how certain wind directions affect various surf spots. You may be surprised to find that adjacent peaks may have significantly different conditions.

As most of you know, onshore winds (blowing from sea to land) tend to mush out and crumble the surf. The Windward surf crew knows this all too painfully well. Of course, they reap the benefits when conditions are ideal for their coastline. If trade wind swell is the only game in town, well, you'll many times have to surf in marginal conditions (surfing in the fetch, so to speak). However, if you don't mind losing some wave size or power, you might want to check out a more protected location that could catch some of the trade wind wrap. Most surfers usually favor offshore winds (blowing from land to sea). The winds actually help eliminate the accompanying shorter period waves, cutting them down since they usually "stick out" and are weaker and slower. Also, the winds tend to hold the wave up more, allowing swells to well up before unloading energy all at once (good for tubes). However, when the offshore winds are too strong, it is much more difficult to paddle into and catch waves, especially with a bigger board. Oftentimes, the wind will blow the spray into your eyes forcing semi-blind takeoffs.

Sideshore conditions are interesting. When the wind is blowing right into the side of a wave, it can sometimes help open up the tube. However, the other side of the wave is typically mushed out, but may benefit from a longer whitewater push. So if say Ehukai Beach has a northwest swell with a strong sideshore NNE wind, you can choose either short, gaping lefts or long, crumbly rights. Again, balancing swell direction with wind direction will help optimize surf size vs. surf quality.

Besides seasonal and large-scale weather patterns, winds can change quite drastically even during the course of a day. In the morning you can sometimes get very light wind situations (absolutely no wind is fairly rare in Hawaii). This can create some of the best surf conditions. Many surfers acknowledge a "phenomenon" known as morning sickness. In the early morning, the surf can sometimes seem warpy and less organized. This is probably due to transitional wind variability. Typically around mid-morning, a more stable trade wind pattern gets established, grooming the waves. As the day progresses the land heats up faster than the ocean, causing the air over it to rise (again, convection). The surrounding air rushes into its place (advection). This is how onshore sea breezes are formed, usually occurring in the late mornings and afternoons, and is more prominent during spells of light trade winds or konas. Cloud cover can reduce the land heating and minimize sea breeze production.

In the late afternoon and early evening, the process stops and reverses (turning into land breezes). That's when you can get that evening glass-off just before dark. This basic understanding of winds and weather in Hawaii, along with associated references, should arm you with enough information and tools to make smart decisions. By also building your own surf conditions database in your head, you'll be able to anticipate where to go to optimize your surf sessions.

Check out these websites for more information on winds:

Stay stoked!

|

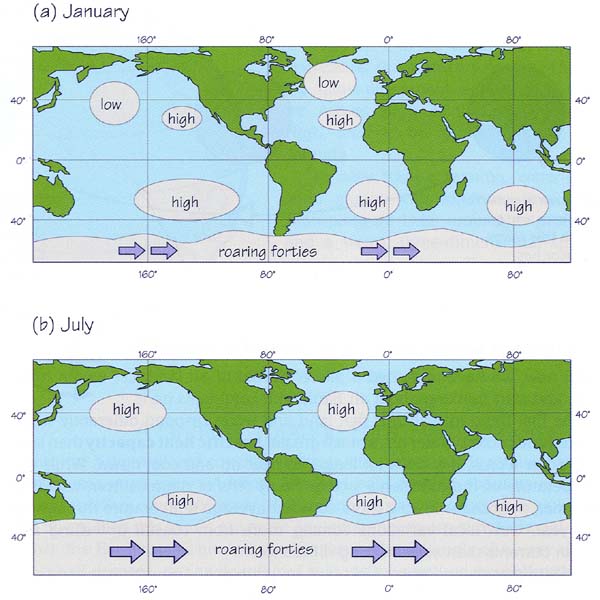

Although many elements complicate global air pressure, there are some fairly prevalent pressure system patterns. These are typical worldwide patterns in January and July. Images courtesy

Although many elements complicate global air pressure, there are some fairly prevalent pressure system patterns. These are typical worldwide patterns in January and July. Images courtesy